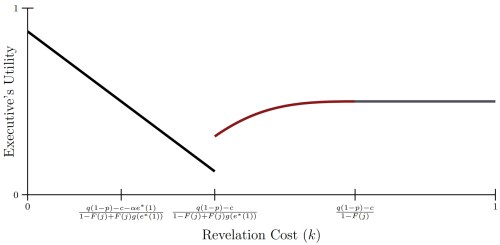

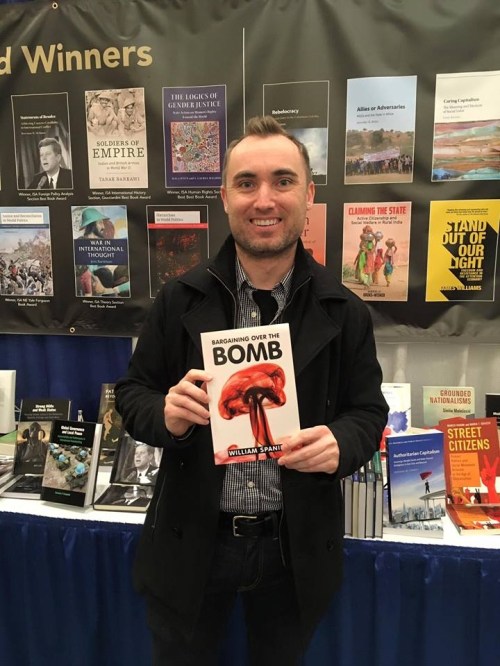

My first book with original research just came out. (Amazon even has proof!) This excites me, as you can see from this picture from a couple of weeks ago, when I held it it my hands for the first time:

Part of my elation came from reflecting on just how long I had been working on the project. I thought it might be interesting for younger scholars to get a full perspective, so I am writing out a brief timeline of book-related events here. It might also give a better overview on the origins, thought process, and evolution of a long-form project. There is also going to be a healthy dose of luck. And regardless of utility to others, it’s going to be cathartic for me.

Here goes:

9/25/2009: Yes, we are starting almost ten years ago. I was in my gap year between undergrad and grad school. Applications were not yet due, but I was set on getting into a program and making international relations research into a career.

Globally, Iran was getting bolder with its nuclear program. President Obama, at a G20 summit, issued a warning:

Iran must comply with U.N. Security Council resolutions and make clear it is willing to meet its responsibilities as a member of the community of nations. We have offered Iran a clear path toward greater international integration if it lives up to its obligations, and that offer stands. But the Iranian government must now demonstrate through deeds its peaceful intentions or be held accountable to international standards and international law.

I remember watching Obama make that speech (which YouTube has preserved for posterity) and thinking that such a bargain would not work. Everything I had read at that point about credibility and commitment problems would suggest so. Why wouldn’t Iran simply take the short-term concessions and continue building a weapon anyway? No paper had constructed that exact expectation yet, and so I thought it would be a straightforward project.

Nevertheless, it would have to go on the backburner. I still needed to revise my existing writing sample and do grad applications.

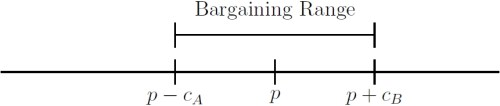

4/2010: By this point, I had accepted an offer from the University of Rochester. I started fiddling around with modeling Obama’s deal and came to an interesting conclusion. It seemed that compliance was not only reasonable, it was rather easy to obtain. All the proposing country had to do was give concessions commensurate with what the potential proliferator would receive if it had nuclear weapons. The potential proliferator could not profit by breaking the agreement, as doing so would barely change what it was receiving but would cost all of the investment in proliferation. Meanwhile, as long as the potential proliferator could keep threatening to build weapons in the future, the proposer would not have incentive to cut the concessions either.

This project was a lot more interesting than I thought it would be!

8/8/2010: I moved to Rochester and got serious about trying to formalize the idea. The problem was that I had only taken a quarter of game theory before. So the process was … painful, especially in retrospect. I still have an image of my work from way back when:

I can make out some of what I was trying to do there. It is ugly. But I also think this is useful advice for new students. As a first year grad, you are in a very low stakes environment. Trying to do something and doing it poorly still gets you a foothold for later.

In any case, active progress on this was slow for the next couple of years. I had to take some classes to actually figure out what I was doing.

3/9/2012: I watched the previous night’s episode of The Daily Show for no real reason. In a remarkable stroke of luck, it featured an interview with Trita Parsi, an expert on U.S.-Iranian relations. He made some off-the-cuff remarks about Iran’s concerns of future U.S. preventive action. Fleshing out the logic further gave me the basis of Chapter 6 of my book, with an application to the Soviet Union.

9/2012: I made “The Invisible Fist” my second year paper. At the time, this was the biggest barrier for Rochester graduate students, but the idea from three years earlier got me through it.

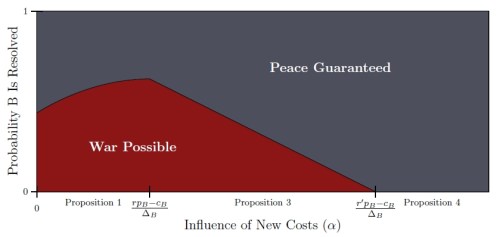

The major criticism as I circulated the paper was that the model only explained why states should reach an agreement. And while nonproliferation agreements are fairly commonplace, so too are instances of countries developing nuclear weapons. Trying to simultaneously demonstrate that (1) agreements are credible and (2) other bargaining frictions might make states fail to reach a deal anyway was too much for a single article. I began looking for more explanations for bargaining failure beyond the one I had encountered for the Soviet Union.

5/17/2013: My dissertation committee felt that I had found enough other explanations, as I passed my prospectus defense. This was the first time I produced an outline that (more or less) matches what the book would ultimately look like.

12/2014: International Interactions R&R’d an article version of Chapter 6. It would later be published there. Tangible progress!

5/2015: Reading through the quantitative empirics of my book, Brad Smith suggested a better way to estimate nuclear proficiency. This eventually became our 𝜈-CLEAR paper. I would later replace the other measures of nuclear proficiency in the book with 𝜈.

6/10/2015: After two years of grinding through lots of math and writing, I defended my dissertation. Hooray, I became a doctor!

7/14/2015: The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—a.k.a. the Iran Deal—is announced. This was could not have been timed any better. Chapter 7 of my book was a theory without a case, only a roundabout discussion of the Iraq War. But the JCPOA nailed everything that the chapter’s theory predicted. I began revising that chapter.

8/2015: I began a postdoc at Stanford. My intention was to use the year to get the dissertation into a book manuscript and talk to publishers. But after six years of thinking about nuclear negotiations and not much else, I was really burned out. I still received excellent feedback on the project during the postdoc, but I set aside almost all of it. The year was productive for me overall, just not on the one dimension I had intended.

10/2015: The JCPOA went into effect. With nuclear negotiations all over the news, I hit the job market at exactly the right time.

7/2016: I moved to Pittsburgh. Remember that Obama speech in front of the G20? In what is a remarkable coincidence that bookends my journey, that summit was just a couple of miles away from where my office is now.

1/2017: I was still burned out. This became a moment of reflection, where I realized that 20 months had passed without making any progress on the manuscript. I convinced myself that if I didn’t get moving, the thing would hang over my head forever and not provide me any value toward a tenure case. So I cracked down and got to work.

3/2017: I sent an email to an editor at Cambridge. He quickly replied, and we set up a meeting at MPSA. Once in Chicago, he liked my pitch and asked to see a draft when I was ready.

5/22/2017: After making some final changes to the manuscript, I sent off a proposal, the introductory chapter, and the main theory chapter to Cambridge.

6/6/2017: My editor wrote back asking for the full manuscript to look over. I did so the next day. One day later, I saw an email notification on my phone that he had responded. I panicked—there is no way that a one-day response could be good news, right? But it was!

You may notice a theme developing here: my editor was fast.

9/6/2017: After three months, the reviewers come back with an R&R. Hooray!

Having published a few articles beforehand, the R&R process was not new to me. But it is an order of magnitude more complicated for book manuscripts. Article reviews are rarely more than a couple of pages. In contrast, I had twelve pages of comments to wade through for the book. This was daunting: a mountain of work and a lengthy road before any of it actually makes noticeable progress to any outside observer. After having gone through almost two years of burn out on the project, this had me slightly worried.

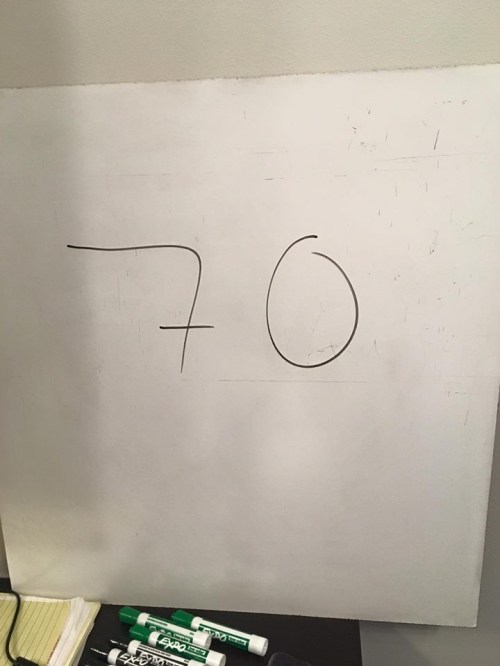

9/12/2017: I developed a solution to the problem that would work. The key for me to maintain focus and appreciate progress was to create a loooooong list of all the practical steps I had to take in revising the manuscript. By the end, I had a catalog of 70 things to do. I put that number on my whiteboard:

I dedicated at least a couple of hours every day to working on the book. Whenever I finished an item, I would go to the whiteboard and knock the number down by one. This gave me some tangible sense of progress even when the work ahead still seemed enormous. It also kept me focused on this project and resist the temptation to work on lower-priority projects that I could finish sooner.

11/28/2017: I sent the revised manuscript back.

1/28/2018: The remaining referee cleared the book. All the hard steps were over!

3/28/2019: I held the real thing in my hand for the first time.

So almost ten years later, I am all done with the project. I cannot describe how satisfying it was to move the book’s computer documents out of the active folder and into the archived folder. I can now finally put all of my effort into the other projects that have been pushed to the sidelines.

But with all of that said, ten years feels like a bargain. Some of that time was pure circumstances: I had to actually learn how to be a political scientist for a good portion of it. I was also an okay writer at the beginning of this, but now I feel that I have a much better grasp of how to communicate ideas.

Nevertheless, some portion of it was my own fault. I could have not put the project on the back burner for more than a year. I suppose if that was the price I had to pay to maintain my own sanity and happiness (and not work on something I was not into at the time), it was a deal well-worth taking.

I was also really, really fortunate with the review process. The first editor I spoke to was receptive of the project, and the reviewers I pulled liked it. Had that not been the case, it is easy to see how a ten year project could have turned into a twelve or thirteen year project. While I hope that future book projects will not last as long, I doubt this part will be as simple the next time around.

In any case, it feels great to finally be done!