From Appointing Extremists, by Michael Bailey and Matthew Spitzer:

Given their long tenure and broad powers, Supreme Court Justices are among the most powerful actors in American politics. The nomination process is hard to predict and nominee characteristics are often chalked up to idiosyncratic features of each appointment. In this paper, we present a nomination and confirmation game that highlights…important features of the nomination process that have received little emphasis in the formal literature . . . . [U]ncertainty about justice preferences can lead a President to prefer a nominee with preferences more extreme than his preferences.

Wait, what? WHAT!? That cannot possibly be right. Someone with your ideal point can always mimic what you would want them to do. An extremist, on the other hand, might try to impose a policy further away from your optimal outcome.

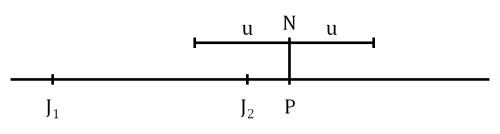

But Bailey and Spitzer will have you convinced within a few pages. I will try to get the logic down to two pictures, inspired by the figures from their paper. Imagine the Supreme Court consists of just three justices. One has retired, leaving two justices with ideal points J_1 and J_2. You are the president, and you have ideal point P with standard single-peaked preferences. You can pick a nominee with any expected ideological positioning. Call that position N. Due to uncertainty, though, the actual realization of that justice’s ideal point is distributed uniformly on the interval [N – u, N + u]. Also, let’s pretend that the Senate doesn’t exist, because a potential veto is completely irrelevant to the point.

Here are two options. First, you could nominate someone on top of his ideal point in expectation:

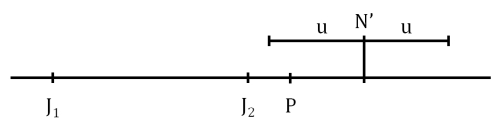

Or you could nominate someone further to the right in expectation:

The first one is always better, right? After all, the nominee will be a lot closer to you on average.

Not so fast. Think about the logic of the median voter. If you nominate the more extreme justice (N’), you guarantee that J_2 will be the median voter on all future cases. If you nominate the justice you expect to match your ideological position, you will often get J_2 as the median voter. But sometimes your nominee will actually fall to the left of J_2. And when that’s the case, your nominee becomes the median voter at a position less attractive than J_2. Thus, to hedge against this circumstance, you should nominate a justice who is more extreme (on average) than you are. Very nice!

Obviously, this was a simple example. Nevertheless, the incentive to nominate someone more extreme still influences the president under a wide variety of circumstances, whether he has a Senate to contend with or he has to worry about future nominations. Bailey and Spitzer cover a lot of these concerns toward the end of their manuscript.

I like this paper a lot. Part of why it appeals to me is that they relax the assumption that ideal points are common knowledge. This is certainly a useful assumption to make for a lot of models. For whatever reason, though, both the American politics and IR literatures have almost made this certainty axiomatic. Some of my recent work—on judicial nominees with Maya Sen and crisis bargaining (parts one and two) with Peter Bils—has relaxed this and found interesting results. Adding Bailey and Spitzer to the mix, it appears that there might be a lot of room to grow here.