According to many popular theories of war, the answer is yes. In fact, this is the textbook relationship for standard stories about why states would do well to pursue increased trade ties, alliances, and nuclear weapons. (I am guilty here, too.)

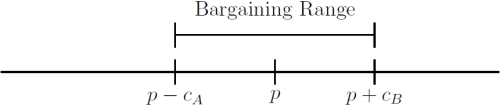

It is easy to understand why this is the conventional wisdom. Consider the bargaining model of war. In the standard set-up, one side expects to receive p portion of the good in dispute, while the other receives 1-p. But because war is costly, both sides are willing to take less than their expected share to avoid conflict. This gives rise to the famous bargaining range:

Notice that when you increase the costs of war for both sides, the bargaining range grows bigger:

Thus, in theory, the reason that increasing the costs of conflict decreases the probability of war is because it makes the set of mutually preferable alternatives larger. In turn, it should be easier to identify one such settlement. Even if no one is being strategic, if you randomly throw a dart on the line, additional costs makes you more likely to hit the range.

Nevertheless, history often yields international crises that run counter to this logic like trade ties before World War I. Intuition based on some formalization is not the same as solving for equilibrium strategies and taking comparative statics. Further, while it is true that increasing the costs of conflict decrease the probability of war for most mechanisms, this is not a universal law.

Such is the topic of a new working paper by Iris Malone and myself. In it, we show that when one state is uncertain about its opponent’s resolve, increasing the costs of war can also increase the probability of war.

The intuition comes from the risk-return tradeoff. If I do not know what your bottom line is, I can take one of two approaches to negotiations.

First, I can make a small offer that only an unresolved type will accept. This works great for me when you are an unresolved type because I capture a large share of the stakes. But if also backfires against a resolved type—they fight, leading to inefficient costs of war.

Second, I can make a large offer that all types will accept. The benefit here is that I assuredly avoid paying the costs of war. The downside is that I am essentially leaving money on the table for the unresolved type.

Many factors determine which is the superior option—the relative likelihoods of each type, my risk propensity, and my costs of war, for example. But one under-appreciated determinant is the relative difference between the resolved type’s reservation value (the minimum it is willing to accept) and the unresolved type’s.

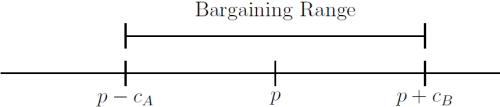

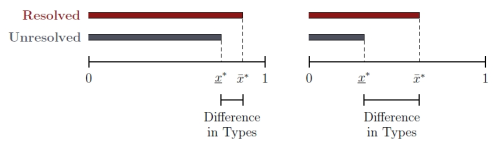

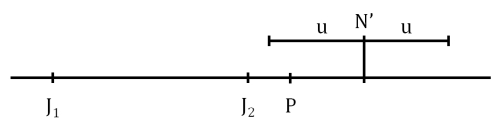

Consider the left side of the above figure. Here, the difference between the reservation values of the resolved and unresolved types is fairly small. Thus, if I make the risky offer that only the unresolved type is willing to accept (the underlined x), I’m only stealing slightly more if I made the safe offer that both types are willing to accept (the bar x). Gambling is not particularly attractive in this case, since I am risking my own costs of war to attempt to take a only a tiny additional amount of the pie.

Now consider the right side of the figure. Here, the difference in types is much greater. Thus, gambling looks comparatively more attractive this time around.

But note that increasing the military/opportunity costs of war has this precise effect of increasing the gap in the types’ reservation values. This is because unresolved types—by definition—view incremental increases to the military/opportunity costs of war as larger than the resolved type. As a result, increasing the costs of conflict can increase the probability of war.

What’s going on here? The core of the problem is that inflating costs simultaneously exacerbates the information problem that the proposer faces. This is because the proposer faces no uncertainty whatsoever when the types have identical reservation values. But increasing costs simultaneously increases the bandwidth of the proposer’s uncertainty. Thus, while increasing costs ought to have a pacifying effect, the countervailing increased uncertainty can sometimes predominate.

The good news for proponents of economic interdependence theory and mutually assured destruction is that this is only a short-term effect. In the long term, the probability of war eventually goes down. This is because sufficiently high costs of war makes each type willing to accept an offer of 0, at which point the proposer will offer an amount that both types assuredly accept.

The above figure illustrates this non-monotonic effect, with the x-axis representing the relative influence of the new costs of war as compared to the old. Note that this has important implications for both economic interdependence and nuclear weapons research. Just because two groups are trading with each other at record levels (say, on the eve of World War I) does not mean that the probability of war will go down. In fact, the parameters for which war occurs with positive probability may increase if the new costs are sufficiently low compared to the already existing costs.

Meanwhile, the figure also shows that nuclear weapons might not have a pacifying effect in the short-run. While the potential damage of 1000 nuclear weapons may push the effect into the guaranteed peace region on the right, the short-run effect of a handful of nuclear weapons might increase the circumstances under which war occurs. This is particularly concerning when thinking about a country like North Korea, which only has a handful of nuclear weapons currently.

As a further caveat, the increased costs only cause more war when the ratio between the receiver’s new costs and the proposer’s costs is sufficiently great compared to that same ratio of the old costs. This is because if the proposer faces massively increased costs compared to its baseline risk-return tradeoff, it is less likely to pursue the risky option even if there is a larger difference between the two types’ reservation values.

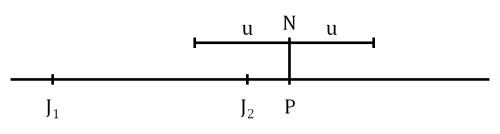

Fortunately, this caveat gives a nice comparative static to work with. In the paper, we investigate relations between India and China from 1949 up through the start of the 1962 Sino-Indian War. Interestingly, we show that military tensions boiled over just as trade technologies were increasing their costs for fighting; cooler heads prevailed once again in the 1980s and beyond as potential trade grew to unprecedented levels. Uncertainty over resolve played a big role here, with Indian leadership (falsely) believing that China would back down rather than risk disrupting their trade relationship. We further identify that the critical ratio discussed above held—that is, the lost trade—evenly impacted the two countries, while the status quo costs of war were much smaller for China due to their massive (10:1 in personnel alone!) military advantage.

Again, you can view the paper here. Please send me an email if you have some comments!

Abstract. International relations bargaining theory predicts that increasing the costs of war makes conflict less likely, but some crises emerge after the potential costs of conflict have increased. Why? We show that a non-monotonic relationship exists between the costs of conflict and the probability of war when there is uncertainty about resolve. Under these conditions, increasing the costs of an uninformed party’s opponent has a second-order effect of exacerbating informational asymmetries. We derive precise conditions under which fighting can occur more frequently and empirically showcase the model’s implications through a case study of Sino-Indian relations from 1949 to 2007. As the model predicts, we show that the 1962 Sino-Indian war occurred after a major trade agreement went into effect because uncertainty over Chinese resolve led India to issue aggressive screening offers over a border dispute and gamble on the risk of conflict.