Shifting power is often cited as an explanation for war. But the causal mechanism isn’t so straightforward.

While the concept of preventive war dates back to Thucydides’ and The History of the Peloponnesian War, the modern understanding is just barely in its third decade. In Rationalist Explanations for War, James Fearon conclusively shows that bargained settlements exist that leave both parties better off than had they fought. The puzzle of war is why wars occur despite this inefficiency.

One of Fearon’s answers is that power may shift over time. Although a rising state and a declining state may reach an efficient bargain in the future, the declining state may be better off securing a costly but advantageous outcome through war today. As much as the rising state might protest, it cannot credibly commit to maintaining the status quo distribution of benefits. Rather, it will eventually want to exploit its new found power by shifting the benefits in its favor.

This idea has taken off in international relations literature. It is now the textbook explanation of preventive war. (See Frieden, Lake, and Schultz, Kydd, or myself.) It also has obvious empirical implications—growing power implies more war—which many quantitative scholars have explored. (See Bell and Johnson, Schub, and Fuhrmann and Kreps for recent examples.) The literature is growing, and knowledge is accumulating. These are great things to see.

A Hidden Assumption

Unfortunately, the causal mechanism behind preventive war isn’t entirely clear, and the notion that power shifts alone cause war is a bit of a myth. One hidden assumption in the simple preventive war construction is that power growth is exogenous. That is, the rising state does not choose whether to grow or how. It simply does, as though power grows on trees.

Yet, in practice, most power shifts are endogenous. Raising an army, building new aircraft carriers, investing in missile defense, and designing nuclear weapons all require active decisions by the state. The basic model ignores this part of the process and instead jumps to the strategic tradeoffs once the state has decided how to shift power.

Thus, a natural question to ask is how endogenous power shifts impact the probability of war. Thomas Chadefaux addresses this in his aptly-titled Bargaining over Power article. Perhaps surprisingly, the war result reverses completely—in any instance that a preventive war would have been fought, bargaining over power leads to a peaceful outcome.

The intuition is straightforward once you work through the mathematical logic. A rising state really wants to avoid war today because fighting would take place on terms most disadvantageous to it. Thus, if it had to choose between undertaking a power shift that would induce preventive war and a smaller power shift that the declining state would acquiesce to, it would choose the latter. After all, a smaller (but realized) power shift is preferable to a costly war.

The New Puzzle

Of course, Chadefaux’s results only take us further down the rabbit hole. There is ample historical evidence to tell us that states fight wars to forestall shifts in power. What then actually causes preventive war?

The literature provides a variety of answers, which I will now attempt to synthesize. First, some power shifts may actually be exogenous. If demographic trends are at the root of a power shift, countries may be unable to effectively limit their future power. In civil conflicts, protesters may be unable resolve coordination problems in the near future, leading to dramatic shifts in power over a short period of time. This helps explain why autocratic regimes exert such great effort in controlling their citizens’ movements.

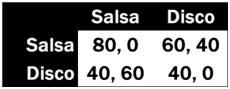

Fearon recognized that the commitment problem disappears when states can bargain over power. But when the object of value also confers military advantages, bargaining can break down when there are indivisibilities in the good. Chadefaux also showed that having distinct discount factors can lead to conflict even without those indivisibilities.

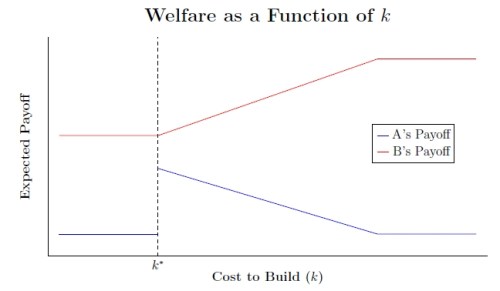

Implementing such an agreement may create other bargaining problems, too. Debs and Monteiro investigate a model with costly power shifts that declining states cannot effectively monitor. Declining states sometimes need to initiate wars so as to deter weapons construction they might not otherwise observe. My research looks to see whether offering concessions-for-weapons can resolve these issues. Fortunately, the answer is yes. However, in the book manuscript I am working on, such deals fail when there is uncertainty over the declining state’s willingness to intervene.

Undoubtedly, there are many more answers to why states fight preventive wars even when power shifts are endogenous. Sadly, though, this literature feels somewhat stifled given that new research often constructs models with exogenous power shifts without any justification for why states cannot negotiate over power.

Empirical Implications

I conclude by discussing some implications of endogenous power shifts. First, quantitative scholars should care greatly about bargaining over power. Although we have established connections between power shifts and war, the above theory indicates that the causal relationship is not obvious. For example, it might be that other bargaining problems cause to both power shifts and war. We need to think carefully about these higher-order issues and search for empirical evidence of them.

Policy-wise, this tells us a great deal about negotiations with Iran. If Tehran constructs a nuclear weapon, it must be doing so because it does not anticipate preventive war. Thus, one way the United States can hold Iran to its commitments under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action is to maintain a credible threat to fight a war should Tehran violate the agreement. Internalizing the threat, Iran would not build a weapon. This is perhaps the ideal for Washington—the American threat to invade does all the heavy lifting, allowing the United States to obtain its best policy outcome without actually paying the costs of war.