The Walking Dead is cable’s most successful TV show, ever. I’m writing this after “Home,” and I’m going to assume you know what is going on by and large.

Here’s what’s important. As far as we care, there are only two groups of humans left alive. One, the good guys, have fortified themselves inside an abandon jail. The other lives in a walled town called Woodbury. They became aware of each other a few episodes ago, and they have various reasons to dislike each other.

War appears likely and will be devastating to both parties, likely leaving them in a position worse than if they pretended the other simply did not exist. For example, in “Home,” the Woodbury group packs a courier van full of zombies, breaches the jail’s walls, and opens the van for an undead delivery. Now a bunch of flesh-eaters are wandering around the previously secure prison.

Meanwhile, the jail’s de facto leader went on a mysterious shopping spree and came back with a truck full of unknown supplies. I suspect next episode will feature the jail group bombing a hole in Woodbury’s city walls.

All this leads to an important question: why can’t they all just get along? It’s the end of the world for goodness sake!

As someone who studies war, I am sympathetic to the problem. Woodbury and the jail group are capable of imposing great costs on one another merely by allowing zombies to penetrate the other’s camp. The situation seems ripe for a peaceful settlement, since there appear to be agreements both parties prefer to continued conflict.

This is the crux of James Fearon’s Rationalist Explanations for War, one of the most important articles in international relations in the last twenty years. Fearon shows that as long as war is costly and the sides have a rough understanding of how war will play out, then both parties should be willing to sit down at the bargaining table and negotiate a settlement.

However, Fearon notes that first strike advantages kill the attractiveness of such bargains. From the article:

Consider the problem faced by two gunslingers with the following preferences. Each would most prefer to kill the other by stealth, facing no risk of retaliation, but each prefers that both live in peace to a gunfight in which each risks death. There is a bargain here that both sides prefer to “war”…[but] given their preferences, neither person can credibly commit not to defect from the bargain by trying to shoot the other in the back.

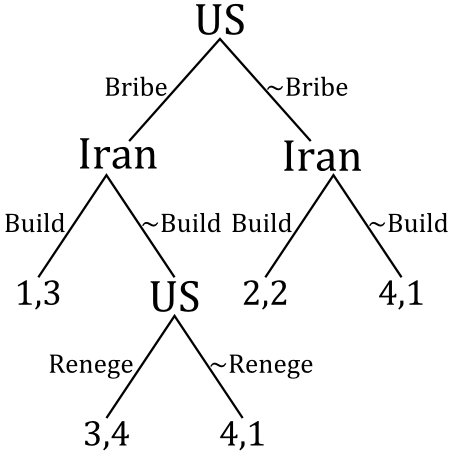

The jail birds and Woodbury are in a similar position:

This is a prisoner’s dilemma.[1] Both parties prefer peace to mutual war. But peace is unsustainable because, given that I believe you are going to act peacefully, I prefer taking advantage of you and attacking. This leads to continued conflict until one side has been destroyed (or, in this case, eaten by zombies), leaving both worse off. We call this preemptive war, as the sides are attempting to preempt the other’s attack.

In the real world, countries have tried to reduce the attractiveness of a first strike by creating demilitarized zones between disputed territory, like the one in Korea. But such buffers require manpower to patrol to verify the other party’s compliance. Unfortunately, the zombie apocalypse has left the world short of people–Woodbury has fewer than a hundred, and the jail birds have fewer than ten. As a result, I believe we be witnessing preemptive war for the rest of this season.

[1] Get it? They live in a jail, and they are in a prisoner’s dilemma![2]

[2] I’m lame.